Allison Lyle, MS2

Hi! My name is Allison and I am a second year medical student at ULSOM. In the summer after my first year, my husband David and I welcomed our first child, a daughter named Natalie, into our family. I wondered (worried, really) how a baby would figure into my second year, with a heavy course load as well as studying for the USMLE Step 1 exam; after some trial and error, we fell into a routine that seems to work well for all three of us.

This is what a typical day looks like for me:

5:00am

Natalie is usually awake by now, and she’s a pretty good alarm clock for me. While David gets ready for work (which for him is over an hour north of Louisville), I get Natalie’s daycare bag packed and my backpack and lunch together. If I’m running on schedule, I’ll start laundry or run the dishwasher, and set something out to thaw for dinner before I leave, which frees up more time in the afternoon and makes life much easier for me once I get home.

6:30am

This is usually the time I drop off Natalie at daycare and make my way into school for the day.

7:00am to 5:00pm

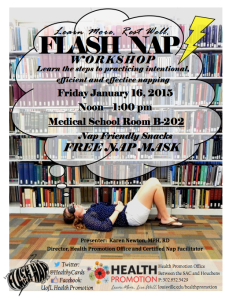

During the daytime hours, I’m usually on campus in class or studying in the unit lab, the lecture hall, or the library—all of which were recently renovated. During the lunch hour, I tend to use this time for myself, by either attending a student organization talk, reading medically-related articles on blogs, or even reading a book just for fun to clear my mind from what I worked on in the morning.

Our class schedule varies day by day. I tend to cherrypick the classes I attend this year moreso than I did last year; with Step 1 rapidly approaching, it’s not enough to study or review what we are learning in class for the next exam, so I try to make the most efficient use of my time by using free time or even classtime going over current information, reviewing lots of practice questions, and integrating my knowledge with First Aid, a resource nearly all medical students use to prepare for Step 1. Most classes at ULSOM are not mandatory, and all are recorded on the Tegrity system so we can review lectures at our convenience, which includes speeding them up. The Tegrity system is a great way to catch information I missed in class, to clarify information that wasn’t clear in the notes, or to experience for the first time (which I had to rely on frequently while I was pregnant during first year!).

During second year, usually on Mondays, we have mandatory classes known as TBLs… sessions for Team Based Learning. (This is one class that stays fairly consistent, compared to the rest of our class schedule.) These consist of 10-15 question, individual quizzes that cover information we learned the previous week, and generally combine information across disciplines, such as Pathology and Microbiology or Pharmacology. The goals of these quizzes are to assess our knowledge and identify the gaps—which we then discuss in our small groups of 6 students as we take the same quiz together. Once we submit the group quiz, we go over any rough areas as a class, highlighting areas that there may have been some difficulty or clarity issues. At the end, we take another quiz together in our small groups to assess how much we have learned during that TBL time. Overall, I enjoy this experience; I find it immensely helpful to hear how others solve problems, which helps me to remember things better for the block exams, which for us are generally once a month.

I am asked quite frequently about how I manage to be a med student and a mom—it can be pretty challenging, but by keeping a schedule and sticking to it, second year so far has gone pretty smoothly. One lesson I have learned during my time as a student has been that making adjustments to find out what works best for my family and me is essential. This realization is what has lead me to stick to my 7am-5pm schedule even on days when I don’t “have” to come to campus; I come anyway, I stay the allotted time and keep focused on the task at hand, and everything has been working great for classes as well as family time.

5:45pm

By 5pm I pack up my belongings for the day and head home to pick up Natalie from daycare. This is the time I generally use as “me” time—playing with my daughter and getting her ready for bed, finishing dinner, and spending quality time with my husband. At night, I generally review the day’s material, work more practice problems, review First Aid, or work on side projects that interest me, such as my research project for the global health distinction track (one of four such distinction tracks offered by ULSOM).

Because my daughter has to be picked up from daycare before 6pm, I try to squeeze in any volunteer or shadowing/precepting hours between the 7am-5pm window. This isn’t always feasible, so I am lucky to have my parents nearby. Having the backup in case I am running late or stuck in traffic is a lifesaver for this medical student!

Friday nights:

Fridays are a lot different from the rest of my time during the week. This is the designated “Date Night” for David and myself. I’m a firm believer in resting to regain my focus after a long week, and this is one great way to maintain my personal interests outside of medical school. Even during first year when we would have the occasional exam on a Monday, I never regretted spending this time away from the books to reconnect with my husband and daughter.

By the weekends I am usually exhausted, but overall, I love life as a new mom and second year medical student at ULSOM!